Pictures by Dominic Nahr

Text by Anna Mayumi Kerber

On avait quitté ce pays le cœur lourd

Espérant pouvoir retourner un beau jour

Faut pas mal de courage pour accepter

Qu’une guerre peut détruire à jamais nos passés

We left that country with heavy hearts

Hoping we would return one day

It takes a lot of courage to accept

That a war can destroy our pasts forever

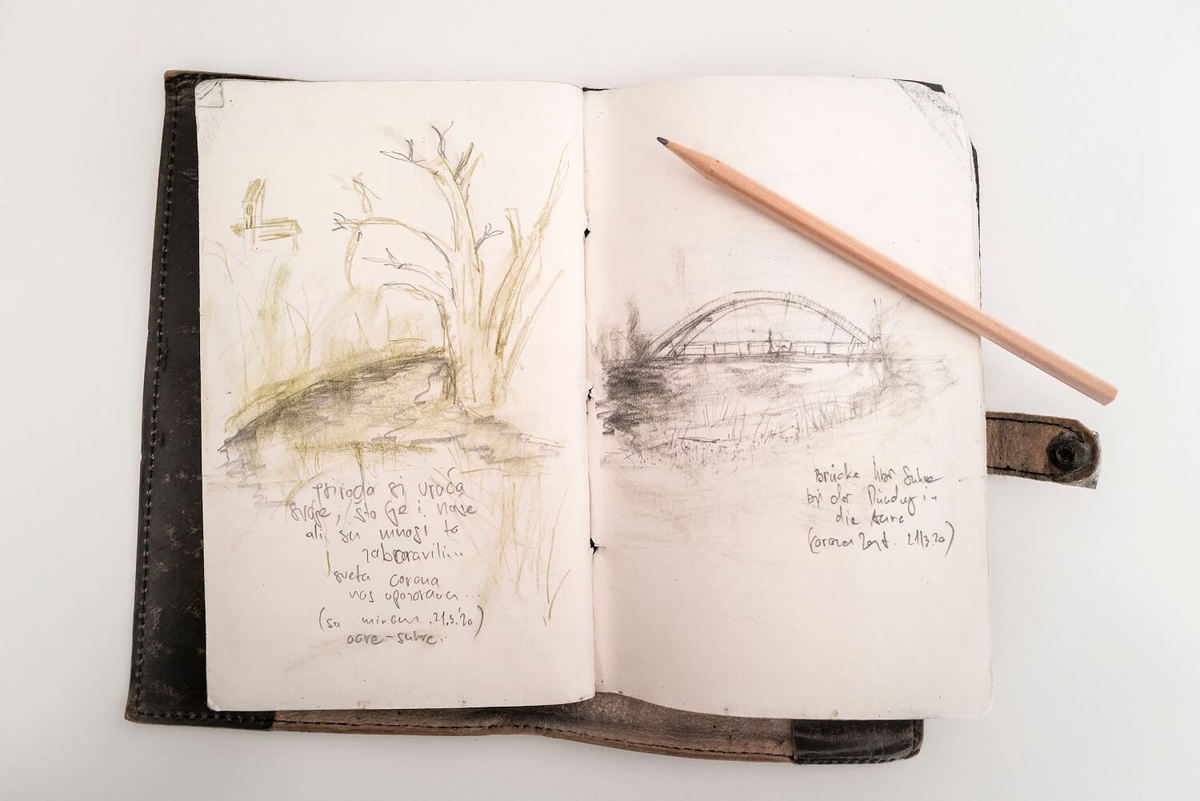

From ‘Ničija zemlja’ (‘No Man’s Land’), Šuma Čovjek

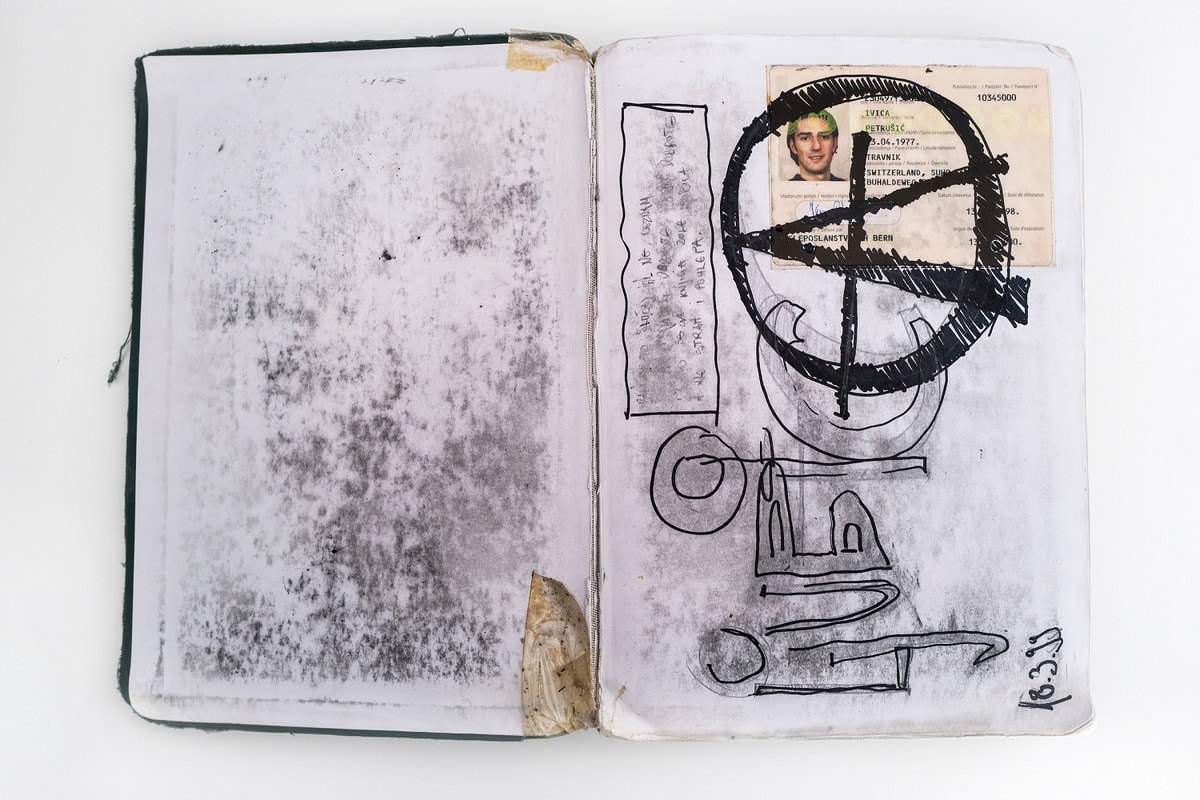

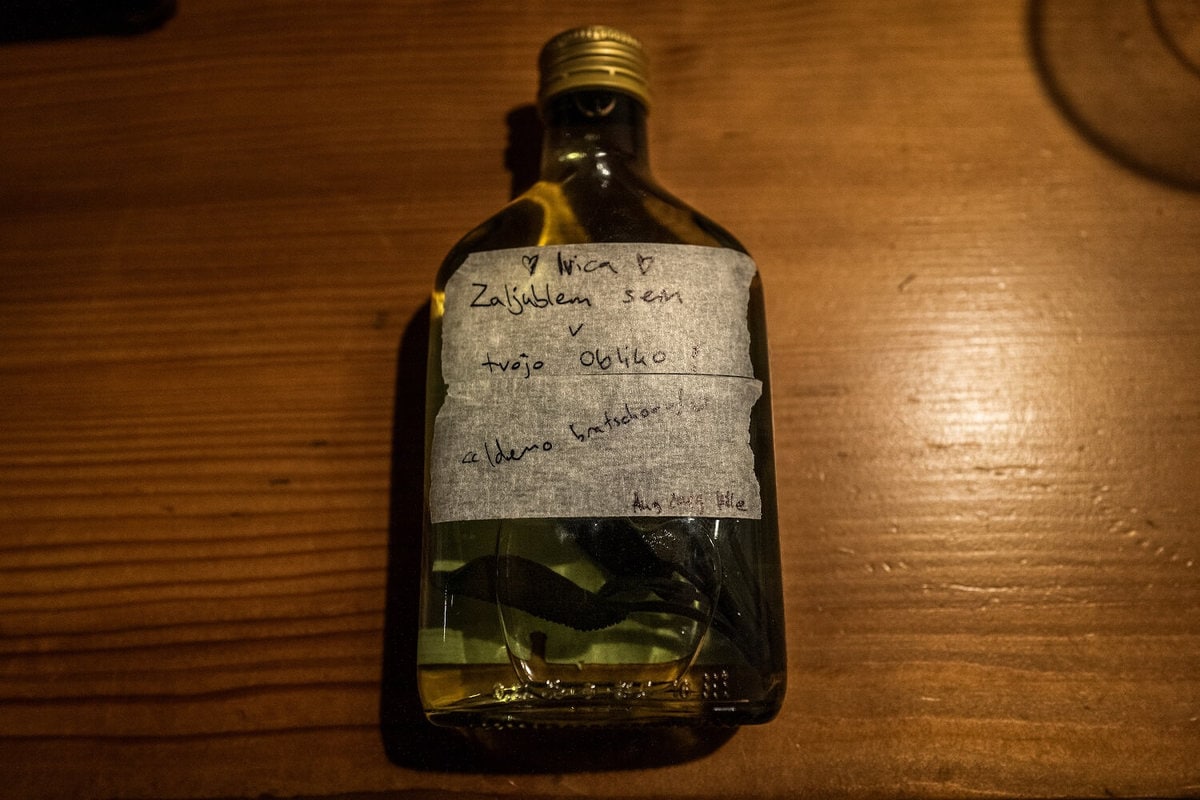

For Ivica Petrušić, ‘home’ has many definitions. It’s the small village of Guča Gora, nestled in the mountainous heart of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It’s Aarau and Winterthur, the cities in Switzerland where his family live. He also feels at home on the basketball court, in the Swiss Alps and on stage – whether the political stage, as a voice for youth and diversity, or as a musician entertaining crowds of thousands.

Since arriving in Switzerland as a teenage migrant, Ivica has become a master of cultural and linguistic codes; this is what it takes to break down boundaries, he believes, and breaking down boundaries is what Ivica does.

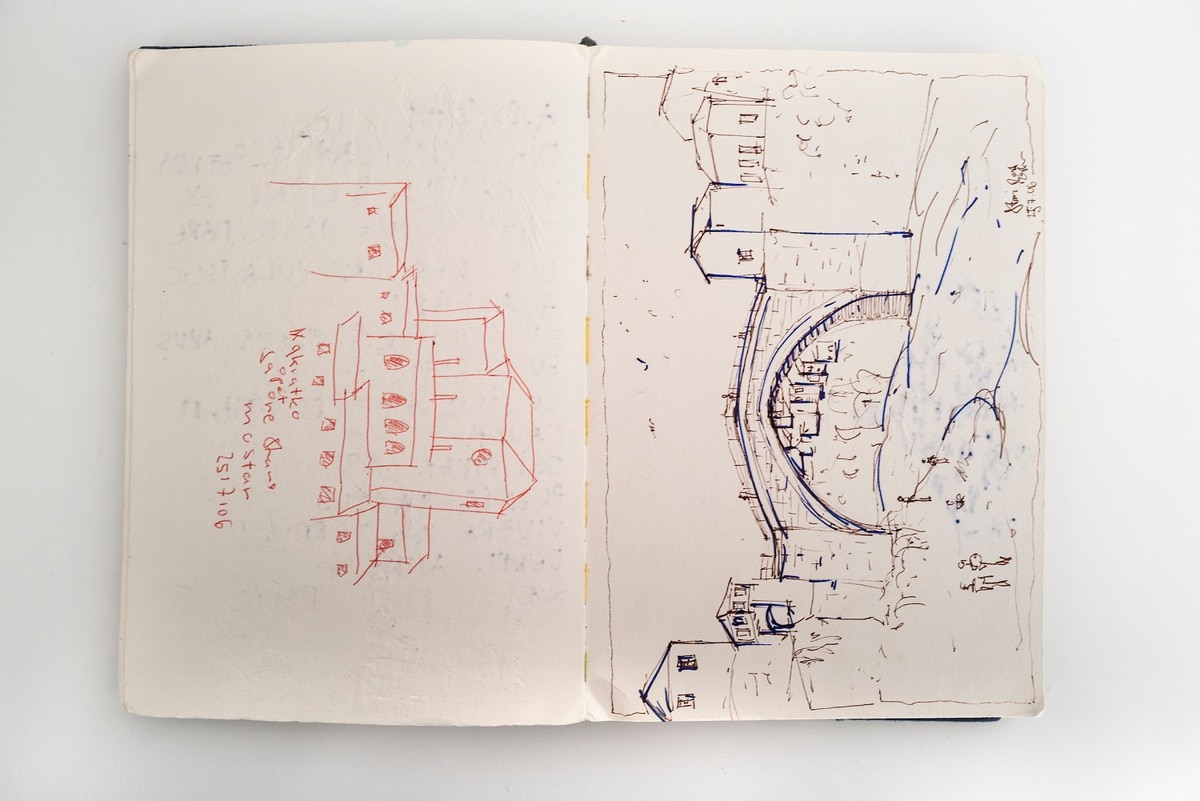

At the age of 14, Ivica was mainly concerned with the deteriorating condition of the basketball hoop in his village of Guča Gora. It was the early 1990s, and the village was still part of Yugoslavia. The Petrušić family were Catholics of Croatian descent. Guča Gora, built around a Roman Catholic Franciscan monastery, was surrounded by predominantly Muslim villages.

Ivica would wake up to the muezzin’s call to prayer and walk to school accompanied by the bells of the Franciscan monastery. He aced exams, had many friends and lived a carefree childhood – there was peaceful coexistence between people of different faiths – until the country went to war with itself and his family was forced to leave.

Bloodshed hadn’t reached their home when the Petrušićs departed in 1991, but it wasn’t long before the tensions, created along ethno-nationalist lines, boiled over: brutal murders between people who had called themselves neighbours led to the disintegration of the nation. The siege of Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the massacre of Srebrenica were seared onto people’s minds as horrific emblems of these wars and their many atrocities.

Ivica’s father was a mason specialising in plastering work. He frequently worked across Europe and beyond, and through a job in a chocolate factory he had earned a permit to live and work in Switzerland with his family – so he used it. Young Ivica had already visited the picturesque country on one occasion and hadn’t liked it; he hadn’t connected with Swiss children. “They were weird,” he recalls.

On arrival, he tried to reach a compromise with his parents – perhaps he could go back to Yugoslavia, stay with his grandmother and finish school there? But his idea quickly became untenable.

Latitude : 47°03′01″ North

Longitude : 8°18′22″ East

Latitude : 47°23′36″ North

Longitude : 8°04′56″ East

Latitude : 44°14′35″ North

Longitude : 17°43′36″ East

Only months after the Petrušić family had left, houses in Guča Gora were riddled with bullet holes. Their family home was occupied by Mujahideen, who slept in their beds and sat around their dinner table. Their relatives were killed by people from neighbouring villages. Mass killings drove hundreds of thousands of Yugoslavs to flee their homes. People flocked west – by train, car and often on foot.

Click here to listen the story soundtrack : "Grana Od Bora", traditional Bosnian song, performed by Ivica Petrušić, accompanied by Manuel Wülser at the piano.

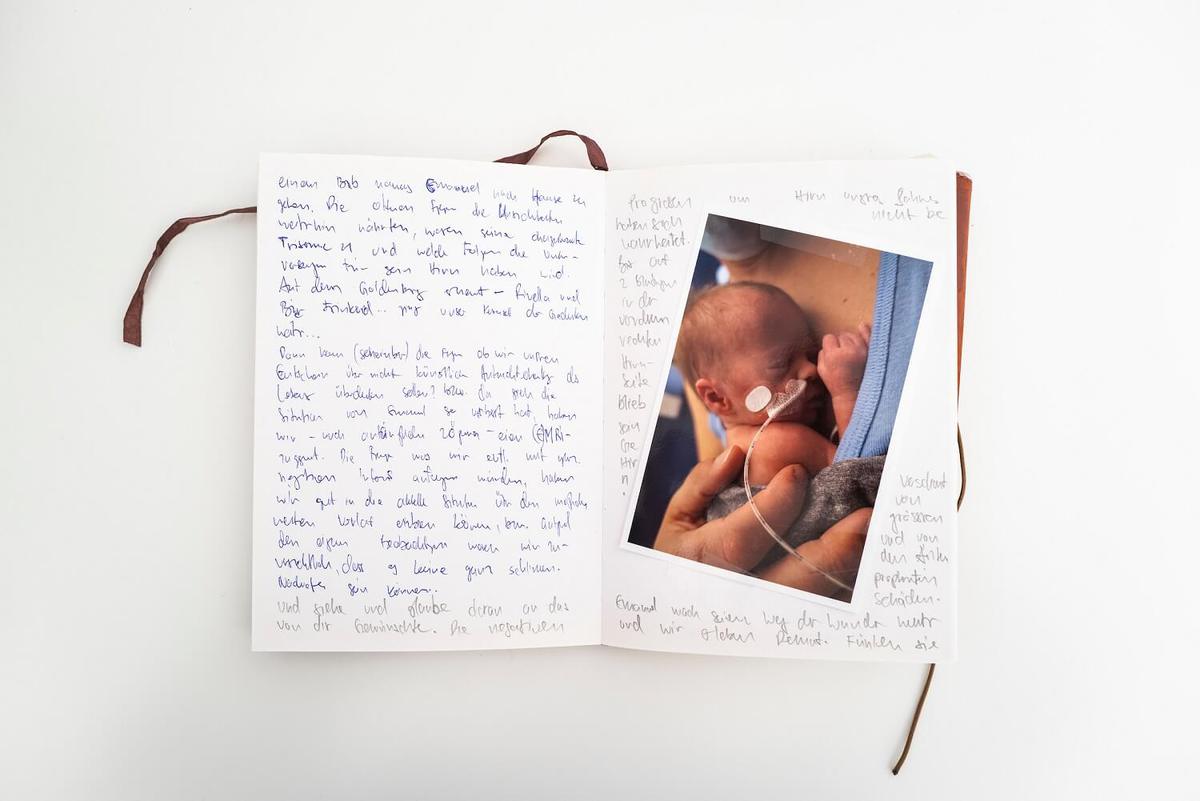

Ivica sits at the graves of his paternal grandparents and his mother Lucija Petrušić.

Ivica during mass inside the monastery church of Guča Gora.

Ivica is hugged by Hafid Derbal, fellow singer in the Balkan-inspired blues band Šuma Čovjek, during the ‘Festival i de Marktgass’ in Bremgarten, Switzerland.

Language was one barrier, but the cultural codes of Switzerland represented a separate challenge. With linguistic guidance from a shopkeeper at a small store, Ivica and his mother worked through a list of items to take on the school’s hiking trip. He turned up in hiking boots and long socks – and was the only one to do so; the other kids all wore jeans and sneakers. And while the Swiss enjoyed their muesli in the morning, Ivica choked on the arid mix. “Who can eat this shit? I thought I was going to die,” he says.

Cultural society Gorica Guča Gora, where older immigrants from the Balkans who have lived for a long time in Switzerland mix with younger generations of migrants. Aarau, Switzerland.

Ivica coaches basketball to children in the Hallenbad Telli sports centre. Many of the children are from migrant families. Aarau, Switzerland.

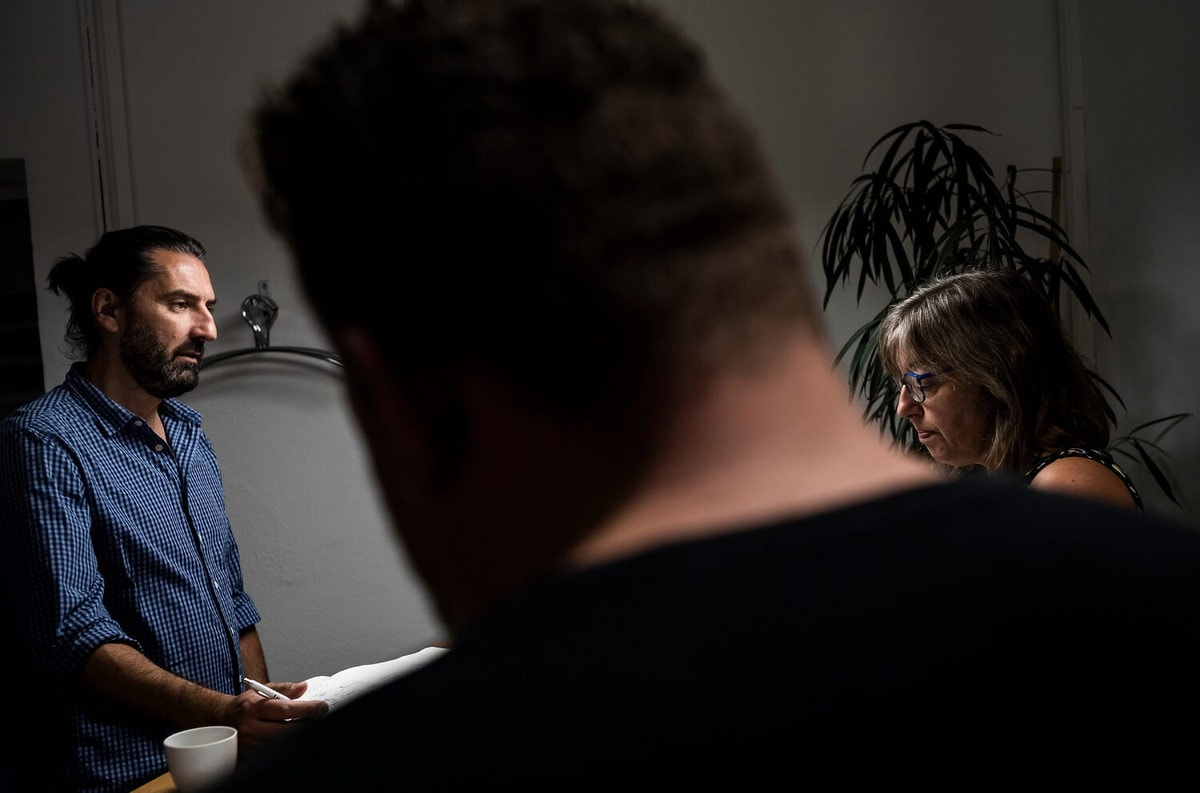

At a meeting of Okaj, a youth association with approximately 600 member organisations in the Zurich canton, Zurich, Switzerland

In Buchs, the small Swiss town where his family ended up, the basketball courts were fancy, nothing like the one in Guča Gora. But nobody used them – they played football instead. Only once the hype around the 1992 US men’s Olympic basketball ‘Dream Team’ made its way to Switzerland could Ivica shine. And the lovely Sandra finally thought he was cool. She approached him and lit her lighter in front of his face – a local way of asking someone out on a date – but Ivica didn’t understand, so he blew out the flame and laughed. Soon afterwards, Sandra was seen holding hands with Giuseppe, a tall Italian guy.

While Ivica struggled to adapt, his parents were relieved that he was in school at all. Although physically in Switzerland, their minds were in Bosnia. They worked tirelessly, organising relief supplies for their family and the wider community back home, and dispatching trucks packed with clothes and food. “They were physically here, but not mentally,” Ivica recalls.

His siblings, both significantly older, had completed their education in Bosnia. Once in Switzerland, they started working in factories. They met and married partners who shared their cultural heritage, and they never became fluent in German, Ivica says; they existed in a bubble. Ivica is the only one in his family who, years later, went on to obtain a Swiss passport.

While Ivica’s father spent much of the time travelling for work, his mother provided the stability he needed and supported him in whatever he took on, raising him with what he refers to as “unbelievable trust and love”. Urvertrauen is the German word he uses to describe what she gave him. It refers to inherent trust, an unshakeable core of confidence.

And then there was the secondary-school teacher, who pushed him – on the sports pitch, academically and in music. He even set up a school band in which Ivica could flourish. “He showed me Switzerland, a country where you have freedom and opportunities – almost as if Switzerland expects you to seize the opportunities you’re given,” Ivica says, recalling his mentor.

Ivica not only took every opportunity he was given, but also created new ones for others.

Today, Ivica goes by ‘slash-Ivica’. The slash stands for politician/musician/athlete/coach/teacher, and many other titles. “A lot of these labels lined up over time,” he says. “And they are all connected.”

He first went on to become a structural draftsman and explored the Swiss Alps, building huts in the mountains. Later, as a youth worker, he nurtured kids from many different backgrounds. He then became a basketball coach and moved into politics.

The initiators of Republic Day – a holiday in Aarau to commemorate the town’s brief period as capital of the Helvetic Republic in 1798 – with the revolution flag. From left: Stephan Müller, Peter Roschi and Ivica. Aarau, Switzerland.

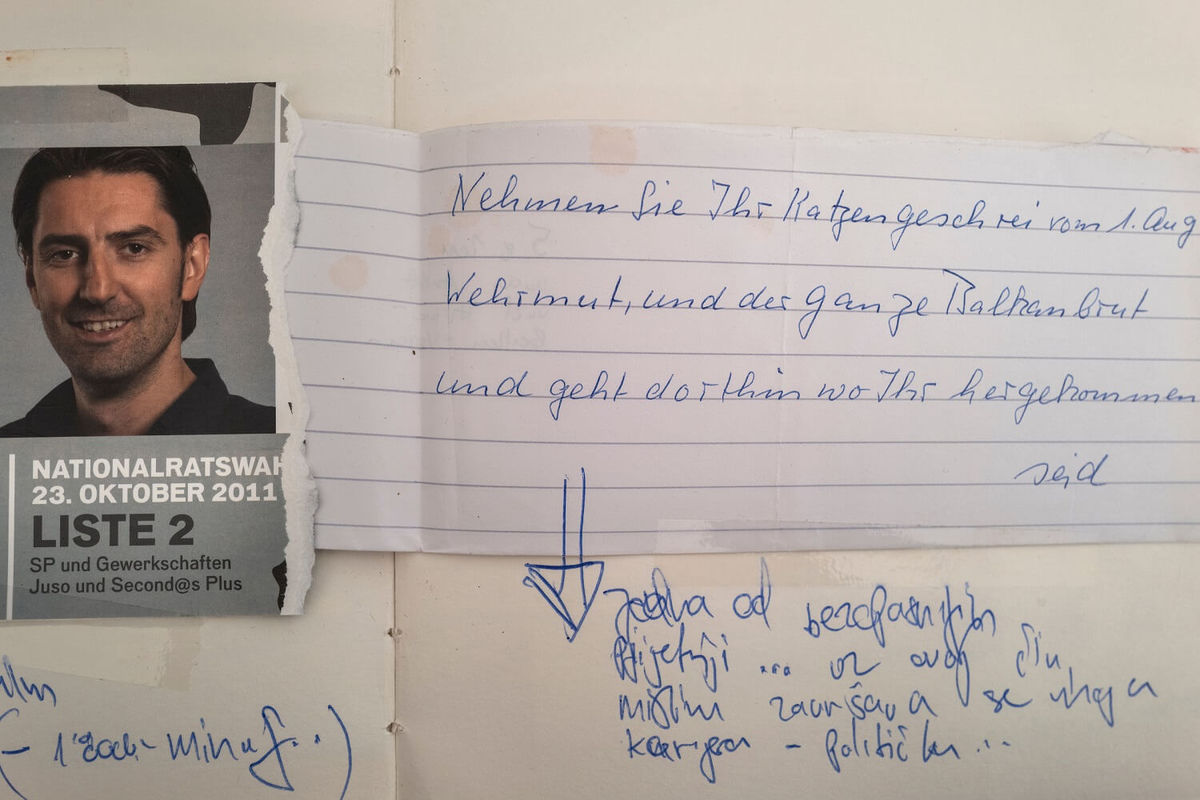

As a politician he pushed for more inclusivity, and for a system where you can spell your name with diacritics without it being a constant nuisance. He pushed for the revival of a historic Swiss holiday dating back to the end of the 18th century, a time when, during the few years of the Helvetic Republic, everyone was allowed to vote, regardless of their nationality. He translated the Swiss national anthem into Serbo-Croatian and demanded a new flag for Switzerland. He hit a sensitive nerve of right-wing populists on multiple occasions, leading to political controversy that attracted death threats as well as international attention.

Now, he is a lecturer in social work at the Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts. “Social life, participation, empowerment – these are my subjects,” he says. And music has stayed with him all the way. He has spent a lot of time in rehearsal rooms and on stage, experimenting with words and sound – as a teenage rapper, then later as an MC and in the Extrem Bosnian Blues Band. In his music, he started mixing Balkan languages with German, and expanded from hip hop to other genres.

His current band Šuma Čovjek (Croatian for ‘Forest Man’) combines Swiss, Bosnian and Algerian roots, and mixes Balkan pop and brass with chanson and rap. The songs’ lyrics are about leaving, home, identity and navigating different cultures. With language being a cornerstone of culture and identity, most songs are written in several languages – French, Arabic, Bosnian, Croatian and Serbian – all mixed together.

Šuma Čovjek - Mira (شلم عليكم) (Official Video)

“You don’t need to know a language perfectly,” says Ivica. “The perfection lies in the mix.” He himself speaks Bosnian, German, English, French and “understands everything from Slovenia to Macedonia”. He knows the Cyrillic script, “And if I’m really drunk, my Polish works perfectly fine, too.”

There are treasured words in every language that can’t be translated. There are rhymes that work better in one language, or emotional states that can be described far more precisely in one language than in another. This medley of language and culture celebrates counterpoints as well as shared experience. At Šuma Čovjek gigs, tens of thousands of feet move to the upbeat music, but at the same time the lyrics dive deep into the darkest recesses of migrants’ lives, exploring the notion of home when it is split between different places, and the social and political challenges that come with that.

Ivica wants to probe these issues in order to find solutions to the social problems faced today, and not only by migrants. “For me there’s always at least two solutions: the Bosnian and the Swiss one,” he says. “And if there are two solutions, there are most likely some more. Depending on the situation you have to figure out which one is the right one to serve you on a specific matter.”

Ivica and his son Milo (10) spend a weekend at the Sewensee, a lake 2,089 meters above sea level in Uri canton, Switzerland. Ivica used to work in the nearby Sewenhütte and lived on the mountain. Isenthal, Switzerland.

Ivica seeks to reconcile his family’s past and present. He made sure that his two sons born in Switzerland are dual nationals and speak Croatian. “I say Croatian because that’s what my family insists on. Actually it’s Serbo-Croatian, which is also Bosnian. But because Bosnia, Serbia and Croatia were fighting in the war, the languages are now named differently. So we just call it Croatian at home. It’s still a mix,” he explains.

Ivica with his family inside Hegi Castle in Winterthur in Zurich canton, Switzerland. His girlfriend’s great-grandfather refurbished the castle. Winterthur, Switzerland.

His youngest son was recently baptised in Guča Gora. His mother was laid to rest in the hills of the village, next to his uncle who stayed behind to protect the village and was killed during the war. His father moved back to Bosnia after retiring. Next to his father’s house, on the site of a now derelict family house, Ivica is building his own.

Ivica and his father Ivo Petrušić discuss Ivica’s future house, which stands on the plot next to his family house. Guča Gora, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

He also took members of Šuma Čovjek to Bosnia to shoot music videos and covers for their new singles and album. Among the crew were an Arab, a Swiss and himself, a Catholic Bosnian, all cavorting through the forests around Guča Gora.

During the filming of the music video ‘Ohé la vie’ in a small town on the outskirts of Zavidovići, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Šuma Čovjek – Ohé la vie (Official Video)

Ivica Petrušić, Hafid Derbal and Manuel Wülser during a TV interview on their first day in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Driving through the village, Ivica would jump out of the car to embrace people. At all times of day, the crew would be invited into people’s homes and offered a fortifying glass of rakia, a popular home-made spirit. The atmosphere would change significantly, however, whenever they left the village and entered a Muslim neighborhood. There would be a palpable tension, no greetings exchanged. It would feel harder to meet people’s eyes, even though they lived as close neighbours.

Ivica’s mother knew who stole the curtains from their house during the war. It was the family of one of his classmates, and the curtains remain with them to this day. “We don’t talk about these things,” Ivica says. The sullen demeanor the band encountered at times during the trip wasn’t surprising to him. This scepticism and reticence wasn’t created only through the Yugoslavian wars. “It’s centuries of wars and invasions where someone would come – the Austrians, the Turks, emperors and dictators – and tell people what to do,” he explains.

Once introduced by a friend or acquaintance, though, doors would open. And then it wouldn’t matter anymore if you were a Swiss photographer, an Algerian musician or a Bosnian migrant.

Hospitality also runs deep in the Petrušić family. “My mother taught me that a house should always be open to anybody,” Ivica says. That’s what is driving him to build a house in Guča Gora. “It would be easier to tear down the broken walls and start afresh. But I think we carry a responsibility to the ones before and the ones after us.” By building on the old foundations, he acknowledges the past, creating a place in which family and friends can experience his history and build new memories together – in other words, a home.