Pictures by Kitra Cahana

Text by Fletcher Reveley

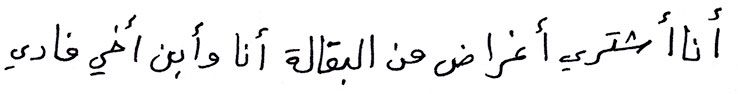

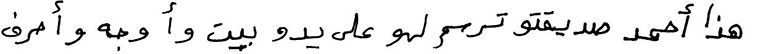

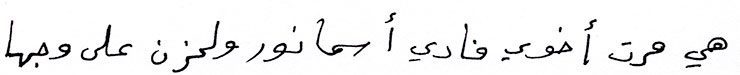

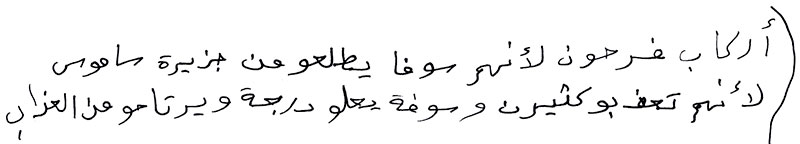

Click on the Arabic captions written by Faten to read the translation

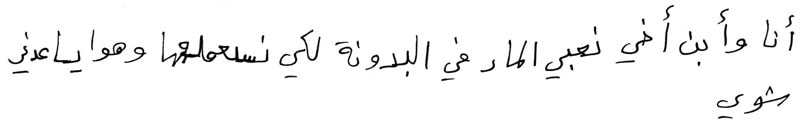

My brother Fade and I were sick.

Latitude : 37° 59' 2'' North

Longitude : 23° 43’ 39’' East

Latitude : 37° 44’ 53'’ North

Longitude : 26° 58’ 57'’ East

Latitude : 32° 37' 35″ North

Longitude : 36° 6’ 12″ East

When her overcrowded and badly waterlogged rubber dinghy finally ran ashore on the Greek island of Samos in the early hours of 15 November 2019, Faten Zalghaneh allowed herself a fleeting moment of joy. Exhausted from fear, wet and shivering in the cold predawn air, the nine-year-old girl from Daraa, Syria, hopped down from the edge of the boat and waded the last few metres to Greek soil. The terror she had felt curled on the floor of the boat as it pitched for hours across the white-capped swells of the Northern Aegean began to melt away. After the gruelling weeks she had spent travelling north with her 32-year-old brother, Fade, through the war-ravaged landscape of Syria with its cramped safe-houses and dubious smugglers; after the four death-defying attempts to cross the Turkish border and the three previous failed attempts to navigate the sea, here she was, finally, on the shores of Europe.

Faten's boat approaching the Greek coast

“I was happy. I imagined a lot of things,” Faten says of the moment her boat landed on the island. “Everyone used to talk about how nice Europe is, and that arriving there is a good thing.”

These are my prayer beads which were given to me by my mother. They are very precious to me. When I'm asleep I sometimes have nightmares, and that’s why I keep them with me.

However, that morning, the things Faten had imagined – smiling people, wide streets and tall buildings, flowers adorning everything – were nowhere to be seen. Instead she saw the painfully familiar sight of flashlights coming towards them in the dark, heard the unmistakable sound of police shouting angrily in yet another strange language. Panicked, Fade took Faten by the hand, and, along with his wife Nura and toddler son Ahmad (who had joined them in Istanbul), they fled into the nearby forest. But they were soon caught. Another jail, more cold and hunger, more rats. More shouting and violence at the hands of men with uniforms. Looking back on that morning when they arrived, Faten feels silly for thinking that Samos offered hope. “I didn’t know what it had in store for us,” she says quietly.

A toilet in the camp. Sometimes I play with my friends there.

The Samos Reception and Identification Centre (RIC) is a sprawling, chaotic refugee camp that perches precariously on a steep hillside above the town of Vathy. The official camp, established on the grounds of an unused military facility in 2015, has a stated capacity of 648 individuals. There are currently nearly 8,000 people living there. The camp spills outwards in all directions from the former military installation into an endless maze of tents and improvised tarpaulin structures referred to as ‘the jungle’ by its residents. Once a dense pine forest, the hillside is now mostly barren of vegetation, with almost every square metre having been claimed for living space.

Several times a week, severe winter rains send torrents of water flooding down the hill, filling the bottoms of tents and saturating bedding and clothes with mud. Scabies and lice are endemic. Rats run rampant over the huge piles of garbage that settle at the base of the hill and bite people as they sleep. Residents of the jungle scavenge anything they can find – tree limbs, garbage, plastic bottles – to burn for warmth, so a cloud of acrid, chemical smoke is always hanging low over the tents. Sometimes the wind whips furiously across the hillside, dismantling the makeshift homes. The metallic clatter of a loudspeaker making announcements echoes across the camp, barely rising above the constant murmur of 8,000 people trying to survive.

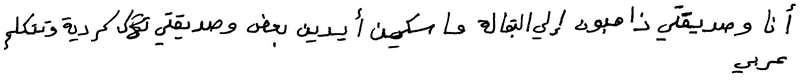

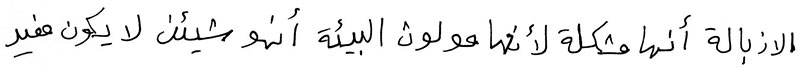

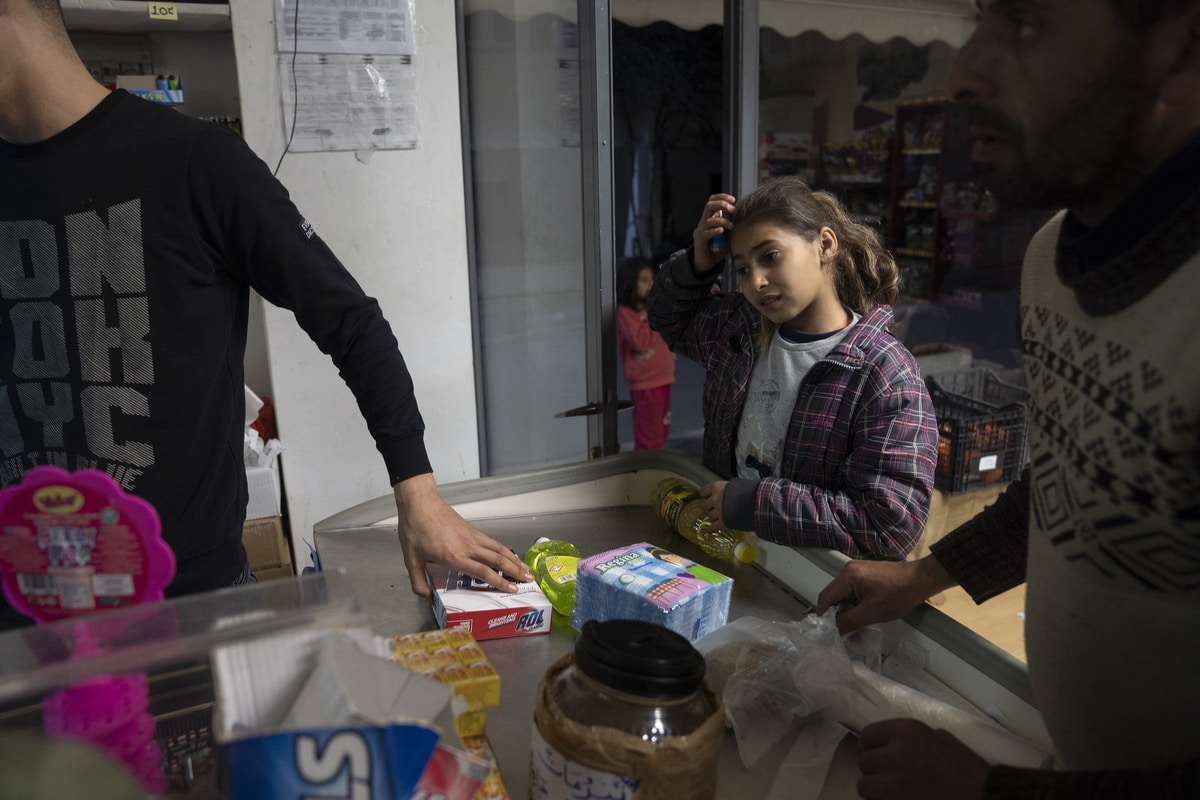

My friend and I are going to the grocer's while holding hands. My friend is Kurdish and speaks Arabic.

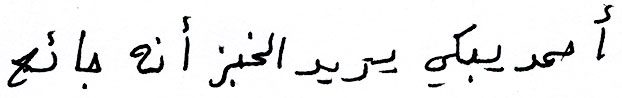

Ahmad is crying. He wants bread. He’s hungry.

When Faten emerged from jail four days after she and her family landed on the island, she was finally able to take in her surroundings. In the daylight, she could see the wide swath of blue tents climbing up the hill, the clouds of foul smoke hanging in the air, the mud-caked clothes of the other refugees.

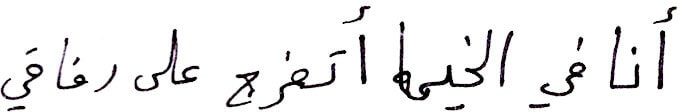

This is me in my tent. It's beautiful. Fade built this tent and it's a bit cold.

“I realised that we too were going to live like this,” says Faten. “And when we saw how things are and heard that we could stay here for six months or four months or three months, our state of mind got worse.”

In 2016 the Greek government began a policy of ‘geographical restriction’, which meant that all refugees, with the sole exception of extremely vulnerable people, would be required to stay on the islands where they had landed until an asylum decision was made. Because of the slow pace of application processing, the islands near Turkey – Samos, Lesvos, Kos and others – became severely bottlenecked, as a steady stream of refugees continued to arrive while very few ever left. When and why people are finally granted asylum interviews is a source of constant confusion in the camp. The process is opaque to the point of seeming arbitrary, leaving camp residents in a state of perpetual uncertainty. Some residents have said that their initial interviews for asylum have been scheduled as far out as 2023.

I’m in the tent watching my friends.

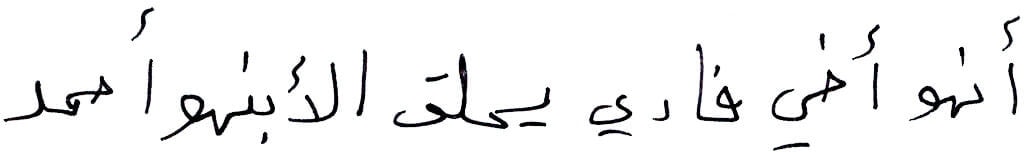

My brother Fade is cutting his son Ahmad's hair.

Myself and my nephew are filling the jug with water. He's helping me a bit.

Garbage is a problem because it pollutes the environment. It's not a helpful thing.

This photo is very beautiful. A lot of the photos are beautiful.

Faten and her family have now been at the Samos camp for nearly five months. The days drift together; the monotony and misery of the place have settled over them like a fog, and the routines have become rote, mechanical.

Trudge up the rocky road near the tent to the water spigot and fill the plastic containers that Nura will need for the day’s cooking and cleaning. Join the food line, wait hours sometimes for a container of undercooked rice and grey chicken. Go for supplies at the nearby market in town, winding through the steep, mud-slick trails that snake through camp, through the Afghani neighbourhood, the Ghanaian neighbourhood, the Sierra Leonean neighbourhood with its scrap-metal gym and guys who are always working out. Hop across the fetid, stagnant pond, weave through the trash alley with its mountains of garbage, boiling with rats. Buy only the essentials: tea, ramen noodles, cigarettes for Fade. Return the same way, again, again, each day the same.

I’m buying stuff from the grocer's with my brother Fade’s son.

This is Ahmad and his friend is drawing on his arm, she's drawing a house and faces and letters.

This is my brother Fadi’s wife. Her name is Nour and sadness is on her face.

Passengers are happy they are leaving Samos Island because they suffered a lot and now they will feel relieved.

Unless out on errands, Faten stays near her family’s shack. A couple of weeks after they arrived, Fade hired some guys to build the shack out of cheap framing timber and plastic sheeting. Two hundred euros for a windowless room of five square metres, with a door hanging jauntily on its hinges that smacks closed with a bungee cord. Water comes in from the ceiling when it rains and seeps up from the ground afterwards. A white bulb fed by a miniature solar panel casts intermittent light. Outside the door, the ground slopes down steeply to a one-lane road that cuts diagonally across the camp and was once used to service the olive groves and nearby municipal water supply. It is in this plastic-walled room that Faten and her family spend day after day, staring through the doorway at the sweeping views of Vathy harbour, wondering when the waiting will end.

A bright and precocious nine-year-old, Faten’s life is unfolding in interstices – between the Middle East and Europe, between war and safety, between youth and adulthood. While her younger nephew still enjoys the comforting oblivion of childhood, Faten knows too well where she’s come from and where she is. The war has scattered her family across the globe – Lebanon, Syria, Sweden, Cambodia – and she feels the fragmentation acutely. It is her responsibility, she believes, to reunite them.

But with so many hours to pass, Faten still indulges in the games the children from her area of the camp play. Zombie, an updated form of tag, is her favourite. She rides a dilapidated shopping cart down the steep stretch of road near her shack at a breakneck speed, a pack of squealing younger children chasing after her. Oftentimes she strolls through the camp with her three closest friends, Lava, Niveen and Amal, talking and laughing. But she says the play, the childhood levity, doesn’t reflect the way she really feels. The frivolity is to appease the other children.

“Am I supposed to cry in front of them?” she asks, huddled in the shack one windy afternoon. “If no one feels for us, why should I show my feelings? All they care for is playing, so I’m going to do what they please . . . and they too have enough on their plates. Just like we’re tired, so are they. They too have sadness and tiredness in their hearts.”

“When I become a lawyer my dream is to build a large house where all my family lives.”

At night, after the chores have been done, the blankets shaken of mud and insects, the shack swept with the bundle of olive branches they use as a broom, Faten likes to draw in her notebook. On page after page, the visions she had of Europe – the Europe she imagined in that brief moment when she first stepped onto Greek soil – come alive. Smiling people, wide streets, tall buildings, everything adorned with flowers. She draws houses, proper houses with walls as straight as a ruler. Pitched roofs to deflect the rain. Gardens with butterflies and swings. The houses vary in their design and setting, but they are all permutations of the same phantasm – the home she is striving for. For the past years of hardship have left Faten with an unshakeable, steely conviction:

“I want to be a lawyer to defend people so that they don’t get oppressed,” she says. “And when I become a lawyer my dream is to build a large house where all my family lives, and we’re all gathered there together, and there isn’t any trouble.”

Update:

This article was written in January 2020. Since then, the Greek government has lifted its ‘geographical restrictions’ on thousands of asylum seekers, allowing them to travel to the Greek mainland. For those who remain on Samos, a new facility has been constructed some 7km away from Vathy town. Intended to reduce the overcrowding and unhygienic conditions of the former camp, the new facility has been described by migrant rights groups as a ‘prison’.

In November 2020, Faten and her family were allowed to relocate to Athens. While Faten still dreams of one day settling in Sweden, a combination of the COVID-19 pandemic and a general lack of resources has prevented the family from travelling beyond Greece.