Pictures by Simona Ghizzoni

Text by Emanuela Zuccalà

Longitude : 12°30′40″ East

Latitude : 41°53′30″ North

Longitude : 44° 25' 19.2″ East

Latitude : 33° 19' 30″ North

The three lives of Hadeel

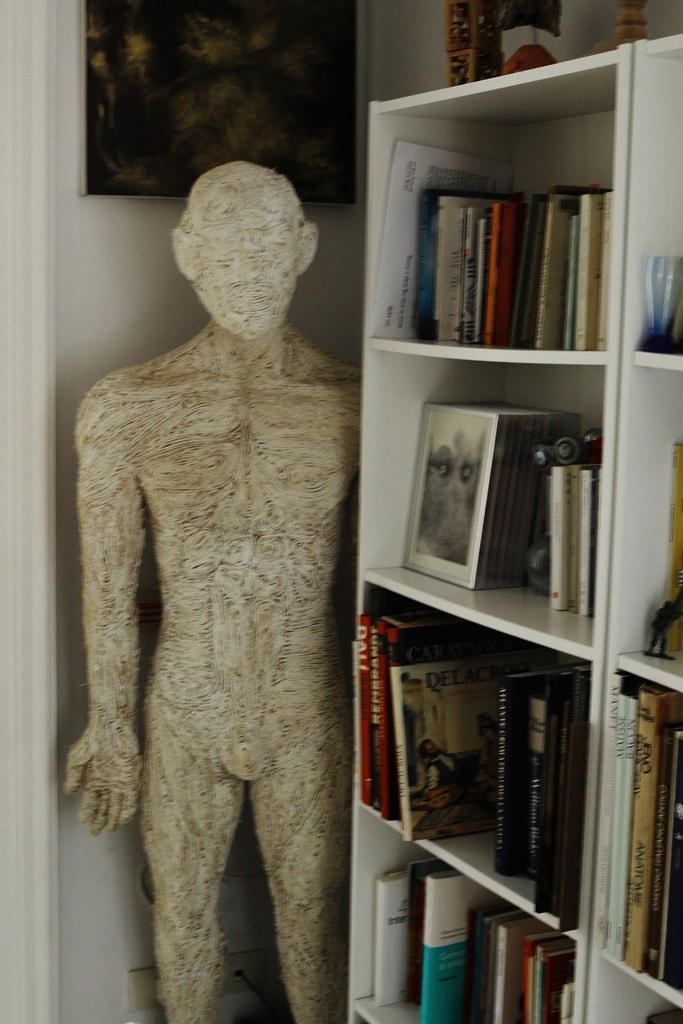

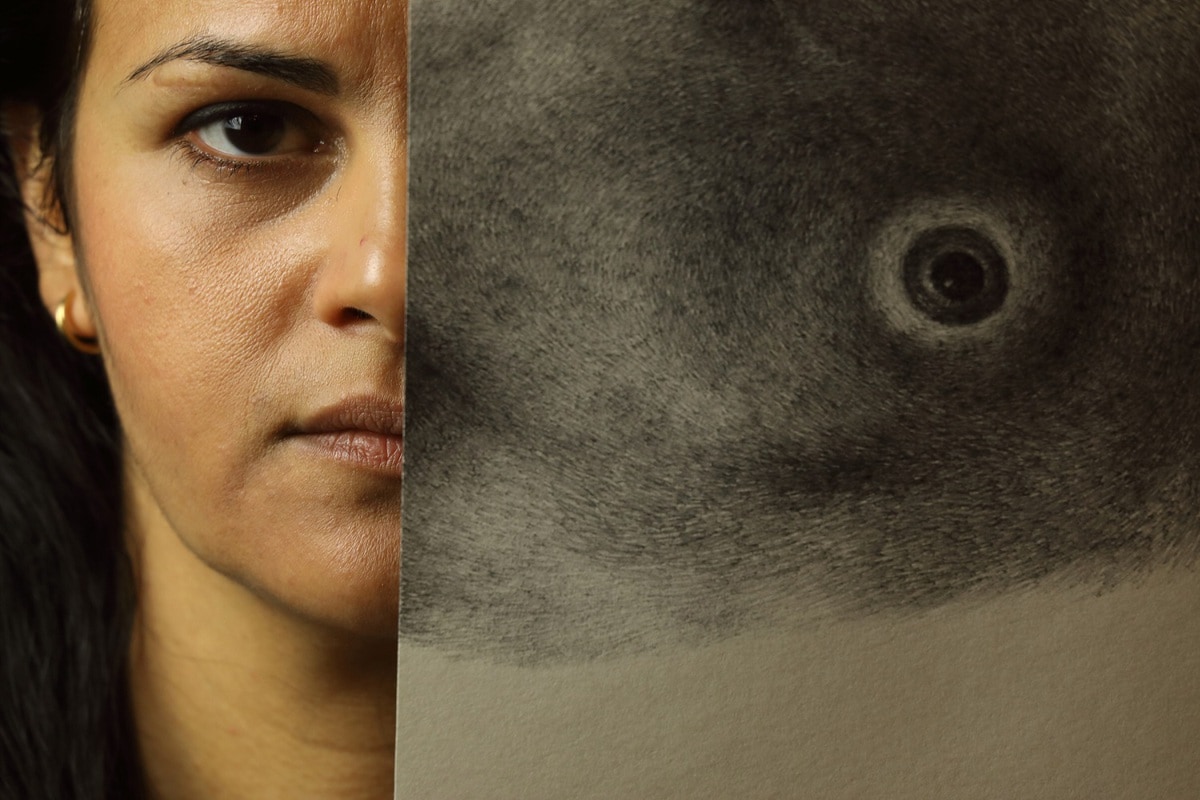

A vivid, wide eye with a blue-green iris offsets olive skin. Below, drawn in pencil, a small female face scans the environment with an animal’s eye. Next to it, an abstract painting is a carousel of colours – furs intertwined with stylised humanoids, more eyes, dynamic purple geometries.

In the living room of an apartment in the Trastevere neighbourhood in Rome, these three artworks – more so than the sculpture of a male figure in papier-mâché presiding over the bookcase – immediately catch the visitor’s attention. And although they could be by different artists with no links to each other, all three are in fact the work of Hadeel Azeez, who herself has been many different women throughout her life.

Baghdad as a child

The vista of Hadeel’s first life was the Al-Kadhimiyn mosque, the palm trees and the small-gardened villas of a quiet, middle-class neighbourhood seen from the second-floor terrace of her house in Baghdad, Iraq. Hadeel was born here in 1981, the youngest of four sisters and three brothers. Her mother, from Iran, was a talented tailor and a passionate herbalist, with knowledge handed down over generations. Her father, an imposing and charismatic man, wrote poetry and traded carpets and all sorts of antiques. The war between Iraq and Iran, from 1980 to 1988, didn’t reverberate much in their lives. Of that conflict, Hadeel remembers only the houses abandoned by the Iranians in her neighbourhood – and that Iraqis were too superstitious to buy them. But she does remember well the Gulf War, from August 1990 to February 1991, after the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. “A flour factory next to my house was bombed. But that conflict hasn’t been a trauma for me,” Hadeel reflects as she serves hummus and couscous with vegetables in her warm Italian apartment. “I was a child, the schools were closed, and it all seemed like a game – our sudden departure from Baghdad towards the city of Najaf, seeking refuge in a mosque, the night sky that sparkled with explosions like fireworks . . .” Meanwhile, Hadeel, like other children, drew pictures, but she had a special talent, and the first to see it was her sister Wafa’, who was 16 years older than her and loved embroidering fabrics with their mother.

Artwork by Hadeel.

Extract from the clip "1980s Baghdad | Iran Iraq War | Baghdad | TV Eye | 1980" (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Gh8bfYNus8) - © FremantleMedia

“You’re an artist,” Wafa’ would repeat to Hadeel during their hot afternoons, and from time to time she would let out the dizzying sentence, which she would later come to regret: “You must study art.”

Baghdad University of

Fine Arts

Baghdad University of Fine Arts

And so Hadeel’s second life began at the Academy of Fine Arts in Baghdad, where she specialised in painting. This led to the first cracks in her relations with her family. “The problem wasn’t that I was a woman who wanted to study,” she explains. “My sisters went to university, my father was a man of culture, and both my parents came from the communist ideologies of the Seventies. But art – no: that didn’t fit within the parameters of a conservative society. Western art expresses values foreign to Iraqi culture, and it often studies naked bodies. My parents wanted me to be a no-problem daughter, like my sisters and cousins. In our society, the individual counts for nothing; only the community is important. What you aspire to as an individual doesn’t matter; you can’t desire something that stains your family’s honour.”

Artwork by Hadeel.

Yet the years she spent at the Academy were, for Hadeel, the most wonderful of her many lives, despite the backdrop of Saddam Hussein’s all-controlling dictatorship. She studied Impressionist painting with a professor who inspired her by talking about how colours behave within us before we see them on canvas. “Don’t look at light and shadow. Feel them.” In her white and grey uniform, long shirt and skirt, she explored the paths of her creativity, and in her spare time she threw herself into studying Islam, yearning to deepen her understanding of the human soul and worldviews, and, in the end, to search for herself.

The Second Gulf War and the journey to Italy

And then, one day, the young artist fell in love, and her second life sprinted to an end. He was an Italian photographer who came to Baghdad at the invitation of his embassy for a group exhibition organised for Saddam Hussein’s birthday. It was 2002. War was in the air; Americans were looking for chemical weapons. The photographer asked Hadeel to marry him, inviting her to Italy to lecture on Iraq and the forthcoming conflict.

This was Hadeel’s migratory journey. No rubber boats, no anguished stumbling through woods and barbed wire. Only a few weeks in Jordan, waiting for a visa that let her land in Italy on 5 April 2003, 16 days after the outbreak of the Iraq War.

Hadeel's studio in Trastevere, Rome, 2021.

“The winds of war were blowing, and I left for Italy to raise awareness about this, but war soon broke out. In Italy, I fell in love and got married. Meanwhile, returning to Iraq had become almost impossible.”

While the conflict ravaged her country, Hadeel built her new self. From the village in southern Italy where she lived with her husband, she took her first steps as a mature artist, painting portraits and then putting on group and finally solo exhibitions entitled Baghdad in the Soul and Contemporary Figures. She then lived for two years in London, where she published in Rooms art magazine. Back in Italy, she broadened her use of media: sculptures covered with mirror tiles to represent the multi-faceted human; installations; iconographical canvases accompanied by verses of Arab poets; video-art experiments. In 2012, at the Arab film festival Yalla Shebab, she interpreted the Arab Spring uprisings in her work The Roses Revolution, which consisted of 30 masks of various sizes made from plaster, varnish and fabric, with rose petals on their eyes to symbolise the young revolutionaries’ dreams. She held solo exhibitions: Transits at the Suor Orsola Benincasa University in Naples and Senses at the Iraqi Embassy in Rome. The capital city seduced her: one day in 2014, she left the village, where she felt encaged, and left with it a faded love. Her third life was over.

Alone in the capital city, she rented a room and supported herself by working in a pizzeria, as a babysitter and as an Arabic language teacher while she continued to paint. She also studied contemporary Middle Eastern art and deepened her spiritual research by analysing the sacred books of Christianity and Buddhism alongside Islam.

These first years of loneliness were suffered, Hadeel now confides, without money or prospects. “But I have this attitude of looking at the world in an instinctive, perhaps naive way, which allows me to overcome difficulties with a fighting spirit.” After an unnerving bureaucratic process, she finally obtained Italian citizenship, sweeping away any nostalgia for Iraq. “In my dreams it’s always the country of childhood, but I don’t feel like I belong anywhere: my home is where I live; my life is where my body is. Everyone thinks that we migrants feel miserable and uprooted, but the human soul has a survival spirit as indestructible as that of plants and animals. We are much stronger than what we believe.”

In her Rome years, Hadeel has exhibited in several museums and galleries, including the prestigious Macro Asilo. Her style has evolved, and she has played with sinuous strands made by ballpoint pens, generating shapeless masses of great expressive power. She fetches a painting from her living room to explain. It’s called Circular and Infinite, a dense circle drawn in pen with a thousand superimposed turns. “At first I called them ‘dissolutions’: when I felt a blender of thoughts inside my head, as a child, I used to draw like this. I stopped when I left Baghdad and resumed here in Rome: a return to my origins, to my essentiality. My art is not premeditated: it’s instinctive, although guided by spiritual and technical research. I observe a lot of Islamic art but also conceptual art. I’m fascinated by the classic Italian masters such as Caravaggio, for his study on chiaroscuro, and by the Flemish greats such as Rembrandt and Vermeer.” Achille Bonito Oliva, a prominent Italian art critic, compares Hadeel’s style to Max Ernst’s abstract symbolism.

Artwork by Hadeel.

Currently, Hadeel is perfecting the visuals for the new album by Scottish jazz saxophonist Tommy Smith and is planning new exhibitions in Italy. During the 2020 pandemic, she created a performance video dedicated to couples and families put to the test by the lockdowns. It’s entitled About Love and includes an excerpt from Kahlil Gibran’s book The Prophet. Her painting The Big Body is on display in the Department of Infectious Diseases of the Tor Vergata University in Rome. Also inspired by the pandemic, it contrasts blue and yellow in a tense energy of human experience: from pain to joy, from illness to rebirth.

Iraq is far away, and she’s never returned, though she knows her loved ones were not harmed in the war. That’s enough. And how does she envisage the future? “It doesn’t exist. My drawings don’t have one single meaning: everyone can see what they want. My future is like this too: open wide. The best is yet to come.”