Pictures by Gaël Turine & Mustafa Hussin

Text by Louis Van Ginneken

Latitude : 50° 51' 1'' North

Longitude : 4° 21’ 6'' East

Latitude : 48° 51' 24'' North

Longitude : 2° 21’ 8'' East

Latitude : 43° 17' 47'' North

Longitude : 5° 22’ 11'' East

Latitude : 43° 47' 28'' North

Longitude : 7° 36’ 27'' East

Latitude : 40° 40' 57'' North

Longitude : 14° 46’ 5'' East

Latitude : 35° 30' 31'' North

Longitude : 12° 35’ 35'' East

Latitude : 32° 45’ 47'' North

Longitude : 12° 44’ 11’' East

Latitude : 13°37′40″ North

Longitude : 25°20′57″ East

30 May 2021, 11 p.m. Mustafa is sitting cross-legged in the middle of the Flagey square. The spot is one of the trendiest places in Brussels, located in one of its richest districts. Young party-goers crowd around, laughing, drinking and singing. Motionless, in the middle of the flow of passers-by, Mustafa observes silently. He has a faint smile, but his mind seems to wander far from here, away from the joyful cacophony, from the multicoloured lights, from this warm spring night.

Mustafa is 4,500 kilometres from his native hometown of El Fasher in Darfur, Sudan. He, and his family, were suffering the direct consequences of the conflicts that have plagued the region since 2003 – the civil war, the armed conflicts, the war crimes committed by government militias and the resulting humanitarian and economic crises. Caught in the grip of this pervasive violence, Mustafa was suffocating. So, in 2016, he set out for Europe, a continent he imagined as being open, welcoming and generous.

Mustafa dreamed of England. Yet, it is just across the North Sea, in Belgium, that he has been living since 2018. He has a big smile and relaxed attitude: everything seems to be going well for him. He currently has a place to live and a residence permit. He works at BXLRefugees, also known as Plateforme Citoyenne, a civic association that helps homeless migrants and refugees. It is a job with a purpose. The suffering he has seen, the ordeals he has experienced and the small gestures that made his own migrant journey possible have made him want to give back in solidarity.

Mustafa dreamed of England. Yet, it is just across the North Sea, in Belgium, that he has been living since 2018. He has a big smile and relaxed attitude: everything seems to be going well for him. He currently has a place to live and a residence permit. He works at BXLRefugees, also known as Plateforme Citoyenne, a civic association that helps homeless migrants and refugees. It is a job with a purpose. The suffering he has seen, the ordeals he has experienced and the small gestures that made his own migrant journey possible have made him want to give back in solidarity.

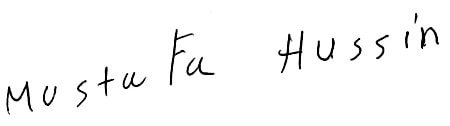

The desert odyssey

Mustafa used to work as a photographer in Sudan so had the impulse to document parts of his journey to Europe. As he begins to tell his story, he grabs his smartphone, on the back of which is a “Refugees welcome” sticker, and scrolls through his photo library. Photos of the streets of Darfur sit alongside pictures of the camps on the road to Europe, and the shelter he found in the homes of citizens in Brussels. Nonchalantly, he scrolls through images of smiles, and corpses. Through these few archives, Mustafa retraces the course of two years of struggles. His memories are scattered and uneven. Sometimes razor-sharp, often foggy, details get lost in the imperfections of a recently learned French.

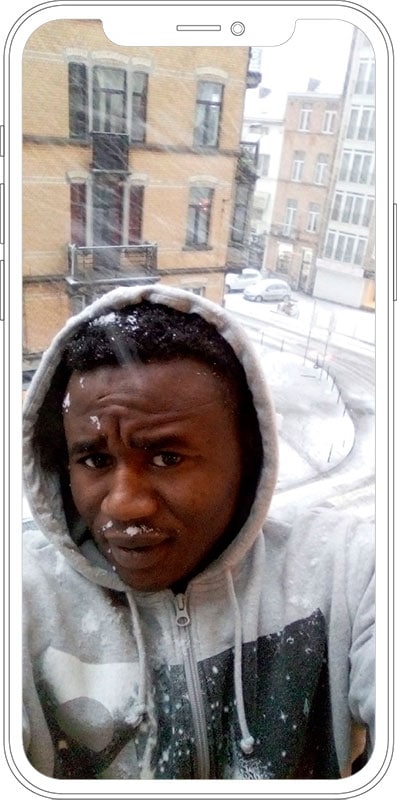

Between El Fasher and the Mediterranean Sea are deserts. One does not face such a journey alone. Mustafa set out for Libya with two of his neighbours. They had been working and saving for months to make the costly journey as part of a cohort through Chad to Libya. This first part of the crossing, up to the coast, took them almost a year. A painful journey, made of detours, backtracking, entering and leaving prisons. And of separations: one of their companions was released from prison only well after Mustafa was. “It was hard, but we were lucky because we didn’t run into the military, or jihadists,” he says casually.

The coastal city of Zawiya, in northwestern Libya, some 50 kilometres from Tripoli, is the last city on the African continent that Mustafa saw. For three weeks he waited, crammed with 600 other men, women and children in a huge empty building. Each night, they waited for instructions from the smugglers, who organise these dangerous sea crossings for a high price. The signal for departure can be rung at any moment.

The instruction was finally given one evening, at midnight. A smuggler hastily called about 30 people together, including Mustafa. They had to embark as soon as possible. In the dark of night, with their feet in the water, he and the others set a raft afloat, delivering 185 passengers – men, women and children – into the stormy swirls of the Mediterranean Sea, where 3,119 migrants had lost their lives that year.

Their makeshift boat was battered by the waves for hours. “There was confusion on the boat. There were men who said we should sail to the left, others to the right.” The sun was at its zenith when the boat finally approached the coast. Mustafa and the other migrants then had their first taste of the so-called ‘Fortress Europe’.

A Frontex helicopter descended towards them in what looked like a pushback operation. Its propellers created a backlash, and the boat was swept away before tipping over and breaking up. “We were all in the water: we had no choice but to swim until a Spanish rescue ship picked us up. Eight people died.” Mustafa doesn’t know which coastline he touched that day. He stayed four days, maybe five, on board the rescue ship. They were finally dumped in Lampedusa, Sicily. Mustafa was halfway to his dream.

With his tall, slender fingers, Mustafa points to an imaginary map in the air. He traces his route and snaps his fingers to mark the decisive moments of his journey. He whistles when he expresses the rapid escapes that he had to make at times. His very first hours on the European continent were one of those moments. Well aware of the Dublin Regulation (a European regulation that determines which EU member state is responsible for examining an asylum application), which would have chained him to Italy, and probably to the refugee camps of Lampedusa, he refused to leave his fingerprints there and managed to board a train to Salerno.

On another continent

Mustafa’s journey to the north of Italy took more than six months. He travelled by foot, by bus or by train, but always in a group. “Our clothes were always dirty, with holes in them. We looked like lunatics. When we asked for help or information from the Italians we met in the streets, we were told ‘No, no, no’ before they even knew what we were looking for. I didn’t understand this behaviour. They didn’t even want to listen to us.”

Despite the general indifference, Mustafa and his fellow travellers were able to count on some timely support on their way north. “Those who gave us a hand were other migrants, or former migrants, people who had experienced what we were experiencing. They helped us, even when we didn’t speak their language. Around train stations, or at gas stations, we would look out for someone who was Black.”

Mustafa explains that some of the most valuable help came from an Italian man of Sudanese origin. He showed them the way and paid their bus tickets to Ventimiglia, a gigantic camp on the border with France, where the Red Cross cares for, accommodates and helps migrants. Similar selfless help was repeated several times on his journey, in Strasbourg, Paris and Brussels.

In the Ventimiglia camp, where Mustafa stayed for a couple of weeks, he himself helped by welcoming the many new Ethiopian, Sudanese and Syrian newcomers, guiding them through the camp, and informing them about the camp’s internal workings. He helped them to understand their next steps, the routes to take and the border areas to avoid.

On the migration route departures are often abrupt. For 200 euros, Mustafa left Ventimiglia in the back of a truck and found himself in Marseille just a couple of hours later. The journey to Paris then took only a few weeks. When he arrived at the Gare du Nord, he came across hundreds of migrants, amassed in precarious shelters around the station.

pic

pic

pic

pic

pic

pic

pic

pic

pic last

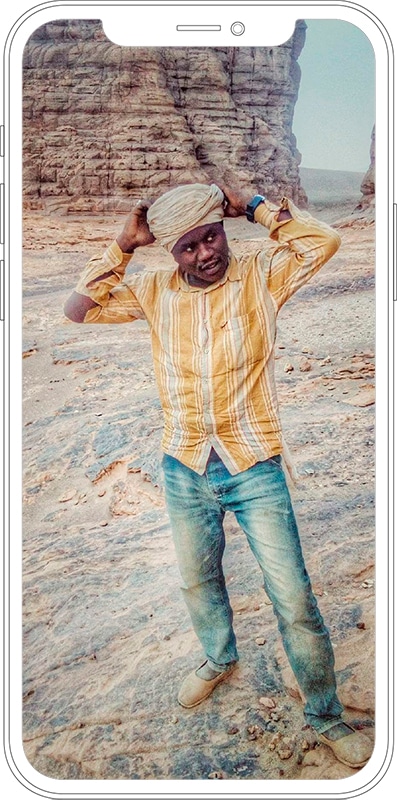

“In Paris, we slept outside, in the streets. Without a tent, without anything,” says Mustafa, laughing. His explanations are surprisingly light. The joy of being in Paris, feeling his European dream within reach, overshadowed all the violence of his experiences.

In Paris, he took selfies at the Eiffel Tower, met up with the friends he had made along the way and even attended parties. But the UK remained his ultimate destination. So he set off for Brussels with the intention of reaching Antwerp. This route was considered a safer option since the dismantling of the ‘Calais Jungle’ camp in 2016.

Settling in

In Brussels, the landing point for migrants from all horizons is Maximilian Park, a green patch in a forest of concrete and glass that was once a luxurious Manhattan-style business district project but is now a sinister ghost town. The park has become a symbol of the migrant and refugee crisis in Brussels. Since 2016, many asylum seekers have camped there, waiting for a response from the Foreigners’ Office, which used to be located on the outskirts of the green square. Mustafa eventually joined them, in 2018. His journey had taken two years in total.

Since the park became occupied, many volunteers head there to provide migrants with food, care or clothing, or to offer them shelter. This organic network of concerned citizens, who initially organised via a Facebook group, Citizens’ Platform of Support for Refugees Brussels, expanded little by little to become BXLRefugees. The association has since opened two accommodation centres. Mustafa quickly benefitted from this network of solidarity, and was repeatedly housed by the same families. In his mind, Brussels was nothing but a temporary stop, and he kept on trying to cross illegally to England every two days, despite the attempts of his hosts to dissuade him.

“These attempts were before I started volunteering for the Plateforme, before I took language classes or met the guys I play soccer with,” Mustafa explains. He eventually got used to life in Brussels. The same year, he ended up applying for asylum there.

While waiting for an answer from the Belgian government, he continued to invest his time in the association, and in helping his peers. “I started as a volunteer, first as an outreach worker, then as a translator and mediator. Every single migrant who arrives is looking for something: for a doctor, for information about asylum. You have to explain it to them. People in the Plateforme’s team don’t necessarily speak Arabic: they are Belgians or Europeans. That’s why I went with them every day.”

Mustafa’s asylum application was accepted unusually quickly, after just six months. “In 2019, I got my first part-time job at the Plateforme. In 2020, I got a full-time job, for an indefinite period.” He is now a night guard at the Porte d’Ulysse, one of the Plateforme’s shelters. “Every night, from 10pm until to 8am. It’s hard, but it’s okay. At night, a lot of things happen, we have to take care of the sick, those who have drunk too much. We have to deal with fights, with the police who show up. Sometimes you have to stay with people, look after them.”

“That’s it,” Mustafa concludes simply, with his everlasting smile on his face.

He has survived deserts, prisons, shipwrecks, fatigue and hunger, but finally his situation has stabilised. He can send money to his family in Sudan and hopes to bring them to Brussels once he finally obtains Belgian nationality.

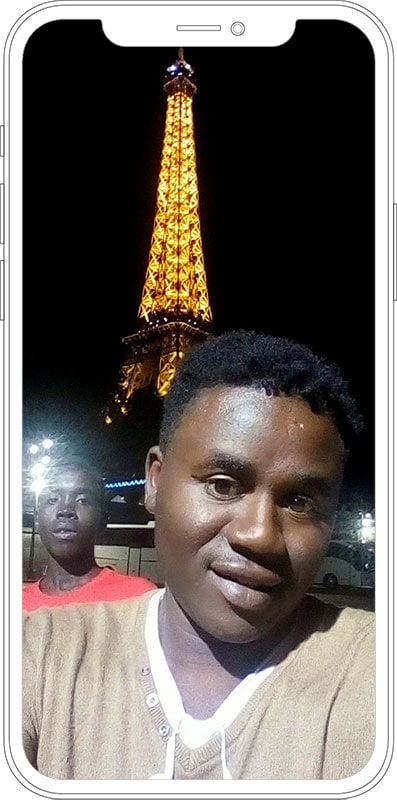

While waiting for his family to be reunited, he now shares a small apartment, not far from the Flagey square, with another young Sudanese man. He has built a rich social life in Brussels and has strong friendships with some of his colleagues at the Plateforme, and other Sudanese people or migrants with similar backgrounds. They often meet up in a bar that a friend owns. Since the regularisation of his status, he also enjoys visiting neighbouring countries in the Schengen Area in Europe.

Mustafa sees a future life for himself in Belgium. For the next few years, at least. But when asked how he feels here, there is a heaviness in his answer.

“It’s good, it’s a chance for me, but … for the other migrants, it’s been more complicated. I’m just one person, an isolated case. And there are so many other people at the shelter, so many people for whom nothing has changed.”