Pictures by Alessandro Penso

Text by Floriana Bulfon

Latitude : 41°53′30″ North

Longitude : 12°30′40″ East

Latitude : 31° 30' 36″ North

Longitude : 75° 20' 7″ East

Navanpreet arrived in Italy ten years ago from Dhilwan in Punjab, the ‘land of the five rivers’ in north-western India. Her childhood was characterised by poverty and hope – her father emigrated in order to give his family a less miserable future. “I dreamt of Rome, the monuments, the treasures on the postcards,” she says. But when Navanpreet finally joined him, a different reality awaited: “I got to know the countryside, where you spend 14 hours a day on your knees, including on Saturdays and Sundays.”

With her sneakers covered in dust and a headscarf tied tightly on her head, she moves around the fields where courgettes and tomatoes are harvested for 3 euros per hour. Knocking on the doors of caravans where people sleep in huddles, she invites them to raise their voices in protest against the employers who see them as nothing more than bodies to profit from. Navanpreet Kaur is 24 years old and Sikh. She works to support the modern-day slaves living in the countryside around Rome. “My father was exploited for many years, without a contract, often unpaid. We need to restore dignity,” she explains.

Navanpreet inside the Sikh temple in Lavinio, Rome.

At the crack of dawn, along the Latium coast, a white van stops on the side of the road. The gangmaster – a 50-year-old Indian man who summons workers via WhatsApp – makes the men get in first, then the women, and if they run out of seats, they are left standing. A sudden stop or a skid on these potholed roads is enough to make them fall and hurt themselves, but it is a calculated risk: like the pariahs of the Hindu castes, these workers are essentially seen as sub-human. And so begins the day for hundreds of exploited labourers.

This is the new face of exploitation: papers seemingly in order, but rights denied.

Paid a pittance – 20 to 30 percent less than their Italian counterparts, or a few hundred euros for a dozen working days – to get vegetables out of the ground and onto our tables across Italy and Europe, these farm workers are forced to live in containers without heating, with squat toilets that drain into the canal. It is a world in the margins, unknown to most consumers of fruit and vegetables. Very few labourers take legal action, because reporting is seen as a dangerous act of rebellion. These days, some workers are paid in the black, with inaccurate payslips and an accountant to renew their residency permits. This is the new face of exploitation: papers seemingly in order, but rights denied.

A group of seasonal workers from Punjab pick up watermelons in San Donato, Latina.

Navanpreet educates the exploited labourers about what those rights are, running through them like a prayer, or a list of commandments: “It is your right to ask for regular contracts and unemployment benefits. The gangmasters shouldn’t be the ones to decide who works or not. You must not pay your contributions on your own.”

As a teenager, she imagined a different path. When she arrived in Maccarese, a village on the coast near Fiumicino Airport, she wanted to become a flight attendant. She enrolled in a high school for international relations and marketing. She did well at her studies but didn’t enjoy her time there: “I did not speak Italian, only English. The teachers helped me, but I wasn’t able to integrate with my classmates. I was always on my own, they never invited me to a party.” She was the foreigner, the only Sikh. People approached her with suspicion, and, while not overtly racist, they mostly ignored her.

During the summer, to help her family, she worked in seaside resorts. “It was tiring, but I enjoyed working in the kitchens. These are multi-ethnic places, and I like diversity,” she says. Then she encountered the Italian trade-union world: “I knew the reality of farm workers and of my community, and when I realised that I could contribute to defending them, freeing them from poverty and injustice, I had no more doubts about which path to take.”

Navanpreet takes a break during her work at the workers’ union office (CGIL) in Maccarese.

Navanpreet likes Instagram, made-in-Italy handbags and Bollywood films. And she is convinced that being a young woman, “neither Indian nor Italian, but Punjabi” is not a limitation at all: “I am respected because I received the Amrit [Sikh baptism]. On top of that, if you are able to solve problems, you gain authority.” She always carries her kirpan, a small dagger, as required by her faith; she only wears her hair loose in the shower, and never cuts it. “They often make fun of the men who ride their bicycles along the dusty country roads, but never of me,” she notes with a touch of pride. But there is anger in her voice when she tells me that some bosses humiliate their Sikh workers by forcing them to cut their beards and hair and to remove their turbans – in order to make them inconspicuous in the fields.

“I want to educate citizens so they won’t need me anymore. My aim is to make them understand that they have rights and the ways in which they can use them.”

Sikh women pray in the temple of Borgo Hermada, Terracina. A group of Sikhs prepare the temple for the Sunday service.

On Sundays, she attends the temple on the Via Aurelia. She goes there to pray but also to talk to the labourers. Many people approach her there. They know by now that she is able to solve problems. A young man in his thirties drags with him the smell of exhaustion. He wants to know if it is true that he can require a pay slip showing all the hours worked. Navanpreet reassures him and repeats the sentences in Italian as well, because, she explains, “I want to educate citizens so they won’t need me anymore. My aim is to make them understand that they have rights and the ways in which they can use them. Many are not even aware that they are being exploited.” Hours bent over in the sun, spreading fertilisers and poisons without gloves and masks, boxes filled in a hurry: their lives are decided by the master, as the Italian owner of the farm likes to be called. To make bearable the pain in their backs and the sores on their feet, and to ease exhaustion, many of them take opium poppy seeds. And for some, even these aren’t enough to help them keep on living. In the last three years, a dozen people in these fields have committed suicide.

Sikh girls paint Navanpreet’s face with turmeric at the Mayian ceremony before her wedding.

Navanpreet and her husband, Ravisher, celebrate their Anad Karaj, or Sikh wedding ceremony, at the temple in Lavinio, Rome.

Navanpreet and Ravisher celebrate Diwali (a festival of light) at the Sikh temple in Lavinio.

African migrants also ask the trade union for help with their poor living and working conditions. African labourers earn substantially less than the Sikhs, and those who dare to rebel don’t get any more work. Ahmed arrived in Italy on a boat, after crossing the Sahel and then Libya. His body carries the scars of someone who has been through inescapable hell. He knocks on the trade-union door and sits in front of Navanpreet. He widens his eyes, and with some embarrassment asks her: “But how did you get a job like this? Can foreigners do that too? Even you who are a woman?” Navanpreet smiles. She explains his rights, tells him about the strike the union has been running for four years and about the need for resistance against exploitation no matter one’s origin and culture. Behind him, a woman is waiting. “These past months, the number of women has increased, and they are convinced that they have to accept any kind of work,” observes the young trade unionist. They work inside sheds bagging or picking fruit under the sun. Their hands have become bent by the daily repetitive movements. On top of that, they earn less than men and suffer harassment too.

“If you get pregnant, they fire you immediately, because you can’t lift 30 to 40 kilogram boxes.”

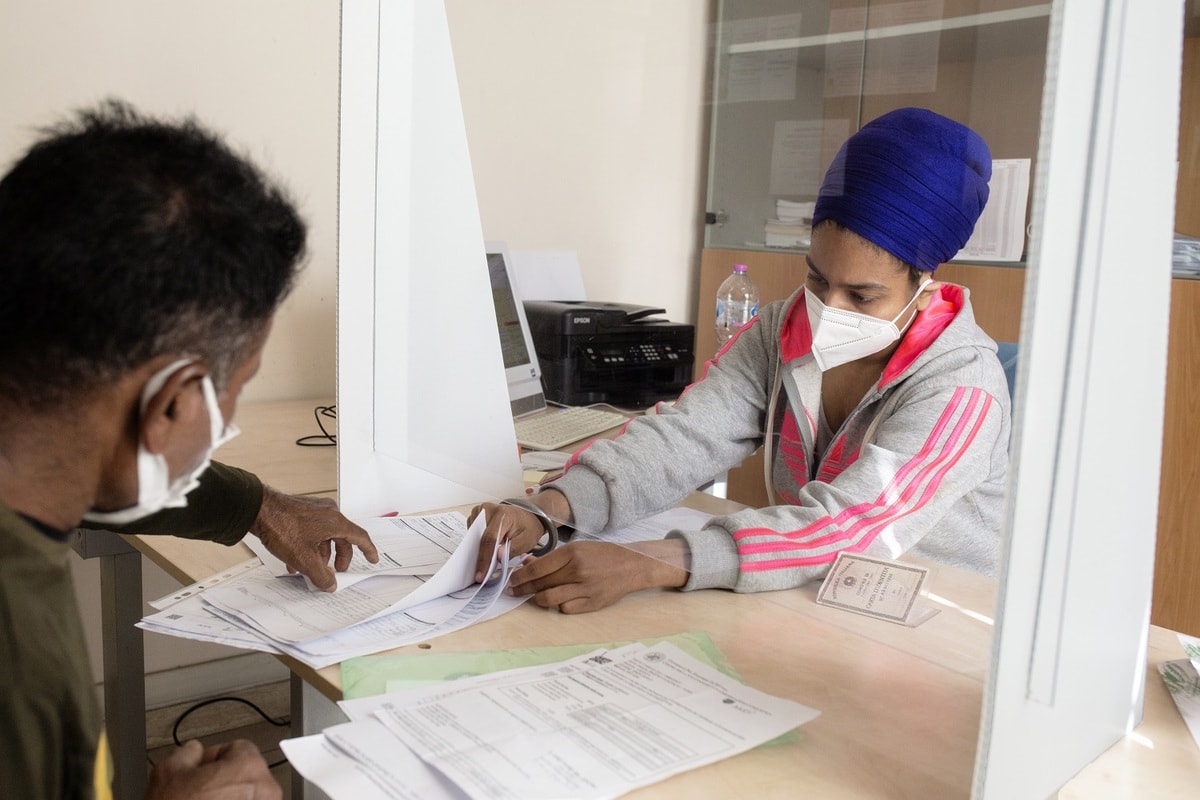

Navanpreet checks an Indian worker’s unemployment claim at the Maccarese office of the CGIL union, where she works.

A worker called Akhila explains: “They write to us that we are employed for four to five days a month, but in reality, we work all the time. If we don’t accept, they throw us out. And if you get pregnant, they fire you immediately, because you can’t lift 30 to 40 kilogram boxes.” She is in her thirties and anguished at the idea of not being able to save money for her daughter’s education. She would like her to be a doctor, “because then she will be able to save me”.

Navanpreet and her husband, Ravisher, after he was tested for Covid-19.

Navanpreet teaches an Indian family about road safety in Italy. Most Indian workers can’t write or read Italian, so Navanpreet helps by translating and teaching them traffic laws.

On 21 September 2019, around 3,000 Sikh workers took to the streets in Latina, south of Rome, in a rally against exploitation after an employer fired a gun to threaten a group of day labourers who were protesting their work conditions.

Navanpreet is a central figure in the battle for democracy.

Trade unionists congratulate Navapreet on her speech to the FIOM-CGIL workers’ union congress in Rome, where she was invited to speak about the situation for Sikh workers in Italy’s agricultural sector.

Video from Navanpreet’s TikTok account.

Navanpreet is interviewed by newspaper Il Fatto Quotidiano during an initiative organised by the CGIL trade union offering free Covid-19 tests to the Indian community in Rome.

Navanpreet is a central figure in the battle for democracy. Through their determination, women such as her are able to overthrow the balance of power, to guarantee justice and build an enriching coexistence. “If I have children, I hope they will be free and honest. Free to choose their own path and to follow it honestly,” she declares. Two years ago, she married Ravisher. He also came to Italy as a teenager and is now a warehouse worker in a supermarket.

Is it an arranged marriage? “Half arranged,” she smiles and adds, “I am also in love with him. I don’t want to plan having kids yet. I know that for Indian families it is important to have children immediately, but I have time, and my husband understands me.” In the meantime, they want to travel, depending on what the pandemic allows, and have bought a new car: “It’s mine, actually, even if many don’t believe it and say it’s Ravisher’s, because he’s the man.” Navanpreet, who once cried because she wanted to return to India, tells me she is now happy to be part of Italy and strives to improve the country, even though she misses the smell of her homeland.

Italy hosts the largest Sikh community in Europe after the UK.

Around 30,000 Indian Sikhs officially live just in the Pontina area, not far from Rome. It is believed the real figure could be 50,000 to 60,000 if irregular migrants are included. Most find work in the agricultural sector, earning around 4.50 euros an hour. At the end of the month, if they’re lucky, they manage to piece together a salary of 800 euros. Sometimes they work illegally, other times with contracts that declare only half of their workdays. Sometimes these contracts are accompanied by blank resignation letters to be signed as soon as the workers are hired. Most live in old hamlets that Italians have abandoned, where there is often no water and/or electricity.

Left to fend for themselves by local institutions, the Sikhs turn to their own community to survive. They meet together on Sundays in their temples – mostly old agricultural warehouses – where they find comfort and refuge in case of need. It is in these places where the first labour strikes began. On 21 September 2019, around 3,000 Sikh workers took to the streets in Latina, south of Rome, to take a stand against exploitation after yet another serious incident. An employer, firing a gun, threatened a group of day laborers who were protesting their work conditions.